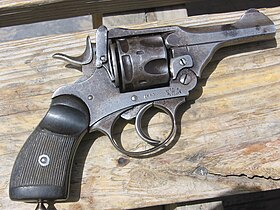

Webley Revolver

| Webley Revolver | |

|---|---|

A Webley Mk. VI top-break revolver. | |

| Type | Service revolver |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1887–1963[1] |

| Used by | See Users |

| Wars | Second Boer War Boxer Rebellion World War I Easter Rising Irish War of Independence Irish Civil War World War II Northern Campaign Indonesian National Revolution Malayan Emergency First Indochina War Korean War Vietnam War British colonial conflicts Rhodesian Bush War Border Campaign The Troubles |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Webley & Scott |

| Designed | 1887 |

| Manufacturer | Webley & Scott, RSAF Enfield |

| Produced | 1887–1924 |

| No. built | approx. 125,000 |

| Specifications (Revolver Mk VI) | |

| Mass | 2.4 lb (1.1 kg), unloaded |

| Length | 11.25 in (286 mm) |

| Barrel length | 6 in (150 mm) |

| Cartridge | |

| Calibre | .455 (11.6 mm) |

| Action | Single or double action |

| Rate of fire | 20–30 rounds/minute |

| Muzzle velocity | 620 ft/s (190 m/s) |

| Effective firing range | 50 yd (46 m) |

| Feed system | 6-round cylinder |

| Sights | Fixed front blade and rear notch |

The Webley Revolver (also known as the Webley Top-Break Revolver or Webley Self-Extracting Revolver) was, in various designations, a standard issue service revolver for the armed forces of the United Kingdom, and countries of the British Empire and the Commonwealth of Nations, from 1887 to 1963.

The Webley is a top-break revolver and breaking the revolver operates the extractor, which removes cartridges from the cylinder. The Webley Mk I service revolver was adopted in 1887 and the Mk IV rose to prominence during the Boer War of 1899–1902. The Mk VI was introduced in 1915, during wartime, and is the best-known model.

Firing large .455 Webley cartridges, Webley service revolvers are among the most powerful top-break revolvers produced. The .455 calibre Webley is no longer in military service. As of 1999[update], the .38/200 Webley Mk IV variant was still in use as a police sidearm in a number of countries.[2]

History

[edit]Webley & Scott (P. Webley & Son before merger with W & C Scott in 1897) produced a range of revolvers from the mid 19th to late 20th centuries. As early as 1853 P. Webley and J. Webley began production of their first patented single action cap and ball revolvers. Later under the trade name of P. Webley and Son, manufacturing included their own 0.44 in (11 mm) calibre rim-fire solid frame revolver as well as licensed copies of Smith & Wesson's Tip up break action revolvers. The quintessential hinged frame, centre-fire revolvers for which the Webley name is best known first began production/development in the early 1870s most notably with the Webley-Pryse (1877) and Webley-Kaufman (1881) models.[3][4]

The W.G. or Webley-Government models produced from 1885 through to the early 1900s, are the most popular of the commercial top break revolvers and many were the private purchase choice of British military officers and target shooters in the period, coming in a .476/.455 calibre. Other short-barrel solid-frame revolvers, including the Webley RIC (Royal Irish Constabulary) model and the British Bulldog revolver, designed to be carried in a coat pocket for self-defence were far more commonplace during the period. Today, the best-known are the range of military revolvers, which were in service use in two World Wars and numerous colonial conflicts.[5][4]

In 1887, the British Army was searching for a revolver to replace the largely unsatisfactory .476 Enfield Mk I & Mk II revolvers, the Enfield having only replaced the solid frame Adams .450 revolver which was a late 1860s conversion of the cap and ball Beaumont–Adams revolver in 1880. Webley & Scott, who were already very well known makers of quality guns and had sold many pistols on a commercial basis to military officers and civilians alike, tendered the .455 calibre Webley Self-Extracting Revolver for trials. The military was suitably impressed with the revolver (it was seen as a vast improvement over the Enfield revolvers then in service, as the American-designed Owen extraction system did not prove particularly satisfactory), and it was adopted on 8 November 1887 as the "Pistol, Webley, Mk I".[6] The initial contract called for 10,000 Webley revolvers, at a price of £3/1/1 each, with at least 2,000 revolvers to be supplied within eight months.[7]

The Webley revolver went through a number of changes, culminating in the Mk VI, which was in production between 1915 and 1923. The large .455 Webley revolvers were retired in 1947, although the Webley Mk IV .38/200 remained in service until 1963 alongside the Enfield No. 2 Mk I revolver. Commercial versions of all Webley service revolvers were also sold on the civilian market, along with a number of similar designs (such as the Webley-Government and Webley-Wilkinson) that were not officially adopted for service, but were nonetheless purchased privately by military officers. Webley's records show the last Mk VI was sold from the factory in 1957, with "Nigeria" noted against the entry.[citation needed]

-

A Webley Mark I Revolver, circa 1887, from Canada, cal .455 (Mk I) Webley

-

Webley Mark VI .455 service revolver

-

Close up of the cylinder (including thumb catch) on a Webley Mk VI service revolver

-

Webley WG Revolver .455/476 (.476 Enfield)

-

A Webley Revolver, opened

-

The IOF .32 Revolver is a derivative of a Webley produced in India

-

Fake Webley Pocket Pistol (in .38 S&W) at Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan

-

.455 in SAA Ball ammunition.

-

A box of Second World War dated 24 July 1944 in .380 Revolver Mk IIz cartridges

In military service

[edit]Boer War

[edit]The Webley Mk IV, chambered in .455 Webley, was introduced in 1899 and soon became known as the "Boer War Model",[8] on account of the large numbers of officers and non-commissioned officers who purchased it on their way to take part in the conflict. The Webley Mk IV served alongside a large number of other handguns, including the Mauser C96 "Broomhandle" (as used by Winston Churchill during the War), earlier Beaumont–Adams cartridge revolvers, and other top-break revolvers manufactured by gunmakers such as William Tranter, and Kynoch.[citation needed]

First World War

[edit]The standard-issue Webley revolver at the outbreak of the First World War was the Webley Mk V (adopted 9 December 1913[9]), but there were considerably more Mk IV revolvers in service in 1914,[10] as the initial order for 20,000 Mk V revolvers had not been completed when hostilities began.[9] They were issued first to officers, pipers and range takers, and later to airmen, naval crews, boarding parties, trench raiders, machine-gun teams, and tank crews. They were then issued to many Allied soldiers as a sidearm. The Mk VI proved to be a very reliable and hardy weapon, well suited to the mud and adverse conditions of trench warfare, and several accessories were developed for the Mk VI, including a bayonet (made from a converted French Gras bayonet),[11] speedloader devices (the "Prideaux Device" and the Watson design),[12][13][14] and a stock allowing for the revolver to be converted into a carbine.[15]

Demand exceeded production, which was already behind as the war began. This forced the British government to buy substitute weapons chambered in .455 Webley from neutral countries. America provided the Smith & Wesson 2nd Model "Hand Ejector" and Colt New Service Revolvers. Spanish gunsmiths in Eibar made acceptable copies of popular guns and were chosen to close the gap cheaply by making a .455 variant of their 11mm M1884 or "S&W Model 7 ONÁ" revolver, a copy of the Smith & Wesson .44 Double Action First Model. The Pistol, Revolver, Old Pattern, No. 1 Mk. 1 was by Garate, Anitua y Cia. and the Pistol, Revolver, Old Pattern, No.2 Mk.1 was by Trocaola, Aranzabal y Cia. Orbea Hermanos y Cia. made 10,000 pistols. Rexach & Urgoite was tapped for an initial order of 500 revolvers, but they were rejected due to defects.[citation needed]

Second World War

[edit]

The official service pistol for the British military during the Second World War was the Enfield No. 2 Mk I .38/200 calibre revolver.[16] Owing to a critical shortage of handguns, a number of other weapons were also adopted (first practically, then officially) to alleviate the shortage. As a result, both the Webley Mk IV in .38/200 and Webley Mk VI in .455 calibre were issued to personnel during the war.[17]

Post-war use

[edit]The Webley Mk VI (.455) and Mk IV (.38/200) revolvers were still issued to British and Commonwealth forces after the Second World War; there were now extensive stockpiles of the revolvers in military stores, yet they suffered from ammunition shortages. This lack of ammunition was instrumental in keeping the Enfield and Webley revolvers in use so long: they were not wearing out because they were not being used. An armourer stationed in West Germany joked by the time they were officially retired in 1963, the ammunition allowance was "two cartridges per man, per year."[18]

The Webley Mk IV .38 revolver was not completely replaced by the Browning Hi-Power until 1963, and saw use in the Korean War, the Suez Crisis, Malayan Emergency and the Rhodesian Bush War. Many Enfield No. 2 Mk I revolvers were still circulating in British military service as late as 1970.[19]

Police use

[edit]The Royal Hong Kong Police and Singapore Police Force were issued Webley Mk III & Mk IV (38S&W then.38/200) revolvers from the 1930s. Singaporean police (and some other "officials") Webleys were equipped with safety catches, a rather unusual feature in a revolver. These were gradually retired in the 1970s as they came in for repair, and were replaced with Smith & Wesson Model 10 .38 revolvers. The London Metropolitan Police were also known to use Webley revolvers, as were most colonial police units until just after the Second World War.[citation needed] The Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Shanghai Municipal Police received Webley Mk VI revolvers during the interwar period.[20]

The Ordnance Factory Board of India still manufactures .380 Revolver Mk IIz cartridges,[21] as well as a .32 calibre revolver (the IOF .32 Revolver) with 2-inch (51 mm) barrel which is clearly based on the Webley Mk IV .38 service pistol.[22]

Military service .455 Webley revolver marks and models

[edit]There were six different marks of .455 calibre Webley British Government Model revolvers approved for British military service at various times between 1887 and the end of the First World War:

- Mk I: The first Webley self-extracting revolver adopted for service, officially adopted 8 November 1887, with a 4-inch (100 mm) barrel and "bird's beak" style grips. Mk I* was a factory upgrade of Mk I revolvers to match the Mk II.

- Mk II: Similar to the Mk I, with modifications to the hammer and grip shape, as well as a hardened steel shield for the blast-shield. Officially adopted 21 May 1895, with a 4-inch (100 mm) barrel.[23]

- Mk III: Identical to Mk II, but with modifications to the cylinder cam and related parts. Officially adopted 5 October 1897, most not issued, with exception of a number that were marked with the "broad arrow" acceptance stamp on the top strap. These few went to the Royal Navy.[24]

- Mk IV: The "Boer War" Model. Manufactured using much higher quality steel and case hardened parts, with the cylinder axis being a fixed part of the barrel and modifications to various other parts, including a re-designed blast-shield. Officially adopted 21 July 1899, with a 4-inch (100 mm) barrel.[25]

- Mk V: Similar to the Mk IV, but with cylinders 0.12-inch (3.0 mm) wider to allow for the use of nitrocellulose propellant-based cartridges. Officially adopted 9 December 1913, with a 4-inch (100 mm) barrel, although some models produced in 1915 had 5-inch (130 mm) and 6-inch (150 mm) barrels.[26]

- Mk VI: Similar to the Mk V, but with a squared-off "target" style grip (as opposed to the "bird's-beak" style found on earlier marks and models) and a 6-inch (150 mm) barrel. Officially adopted 24 May 1915,[27] and also manufactured by RSAF Enfield under the designation Pistol, Revolver, Webley, No. 1 Mk VI 1921–1926.[28]

The Webley Mk IV .38/200 Service Revolver

[edit]| Webley Mk IV .38/200 Service Revolver | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Service revolver |

| Place of origin | British Empire |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1932–1963 |

| Used by | United Kingdom & Colonies, British Commonwealth |

| Wars | Second World War, Korean War, British colonial conflicts |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Webley & Scott |

| Designed | 1932 |

| Manufacturer | Webley & Scott |

| Produced | 1932–1978 |

| No. built | approx. 500,000 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 2.3 lb (995 g), unloaded |

| Length | 10.25 in (260 mm) |

| Barrel length | 5 in. (125 mm) |

| Cartridge | .380" Revolver Mk IIz |

| Calibre | .38 (9 mm) |

| Action | Double action |

| Rate of fire | 20–30 rounds/minute |

| Muzzle velocity | 620 ft/s (190 m/s) |

| Effective firing range | 50 yd (46 m) |

| Maximum firing range | 300 yd (270 m) |

| Feed system | 6-round cylinder |

| Sights | fixed front post and rear notch |

At the end of the First World War, the British military decided that the .455 calibre gun and cartridge was too large for modern military use and concluded after numerous tests and extensive trials, that a pistol in .38 calibre firing a 200-grain (13 g) bullet would be just as effective as the .455 for stopping an enemy.[29][16]

Webley & Scott immediately tendered the .38/200 calibre Webley Mk IV revolver, which as well as being nearly identical in appearance to the .455 calibre Mk VI revolver (albeit scaled down for the smaller cartridge), was based on their .38 calibre Webley Mk III pistol, designed for the police and civilian markets.[30] (The .38 Webley Mk III used black powder cartridges, as did the .455 Webley Mk IV; they should not be fired with the smokeless powder cartridges developed for the .38 Webley Mk IV and .455 Webley Mk V and Mk VI.)

Much to their surprise, the British Government took the design to the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock, which came up with a revolver that was externally very similar looking to the .38/200 calibre Webley Mk IV, but was internally different enough that no parts from the Webley could be used in the Enfield and vice versa.[citation needed]

The Enfield-designed pistol was quickly accepted under the designation Pistol, Revolver, No. 2 Mk I, and was adopted in 1932,[31] followed in 1938 by the Mk I* (spurless hammer, double action only),[32] and finally the Mk I** (simplified for wartime production) in 1942.[33]

Webley & Scott sued the British Government over the incident, claiming £2250 as "costs involved in the research and design" of the revolver.

This was contested by RSAF Enfield, which quite firmly stated that the Enfield No. 2 Mk I was designed by Captain Boys (the Assistant Superintendent of Design, later of Boys Anti-Tank Rifle fame) with assistance from Webley & Scott, and not the other way around. Accordingly, their claim was denied.[citation needed]

By way of compensation, the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors eventually awarded Webley & Scott £1250 for their work.[34]

RSAF Enfield proved unable to manufacture enough No. 2 revolvers to meet the military's wartime demands, and as a result Webley's Mk IV was also widely used within the British Army in World War Two.

Other Webley revolvers

[edit]Whilst the top-break, self-extracting revolvers used by the British and other Commonwealth militaries are the best-known examples of Webley revolvers, the company produced a number of other highly popular revolvers largely intended for the police and civilian markets.

Webley RIC

[edit]

The Webley RIC (Royal Irish Constabulary) model was Webley's first double-action revolver, and adopted by the RIC in 1868,[36] hence the name. It was a solid frame, gate-loaded revolver, chambered in .442 Webley. General George Armstrong Custer was known to have owned a pair, which he is believed to have used at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876.[37][38][39]

A small number of early examples were produced in the huge .500 Tranter calibre, and later models were available chambered for the .450 Adams and other cartridges. They were also widely copied in Belgium.[citation needed]

British Bull Dog

[edit]

The British Bull Dog model was an enormously successful solid-frame design introduced by Webley in 1872. It featured a 2.5-inch (64 mm) barrel and was chambered for five .44 Short Rimfire, .442 Webley, or .450 Adams cartridges. (Webley later added smaller scaled five chambered versions in .320 and .380 calibres, but did not mark them British Bull Dog.) A .44 calibre Belgian-made British Bulldog revolver was used to assassinate US President James Garfield on 2 July 1881 by Charles Guiteau.

It was designed to be carried in a coat pocket or kept on a bedside table, and many have survived to the present day in good condition, having seen little actual use.[40] Numerous copies of this design were made during the late 19th century in Belgium, with smaller numbers also produced in Spain, France and the US.[41] They remained reasonably popular until the Second World War, but are now generally sought after only as collectors' pieces, since ammunition for them is for the most part no longer commercially manufactured.

Webley-Fosbery Automatic Revolver

[edit]

A highly unusual example of an "automatic revolver", the Webley-Fosbery Automatic Revolver was produced between 1900 and 1915, and available in both a six-shot .455 Webley version, and an eight-shot .38 ACP (not to be confused with .380 ACP) version.[42] Unusually for a revolver, the Webley-Fosbery had a safety catch, and the light trigger pull and reputation for accuracy ensured that the Webley-Fosbery remained popular with target shooters long after production had finished.[43]

Users

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2020) |

Australia[44]

Australia[44] Bangladesh[45]

Bangladesh[45] Barbados[46]

Barbados[46] British Empire[47]

British Empire[47] Canada: Used by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police[20]

Canada: Used by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police[20] British Hong Kong[48]

British Hong Kong[48] British Raj[49]

British Raj[49] Gambia[50]

Gambia[50] Imperial State of Iran[20]

Imperial State of Iran[20] Ireland[48]

Ireland[48] Israel

Israel Indonesia

Indonesia Luxembourg

Luxembourg Malaysia[51]

Malaysia[51] Myanmar: Retired[52]

Myanmar: Retired[52] Dominion of Newfoundland

Dominion of Newfoundland New Zealand[44]

New Zealand[44] Pakistan

Pakistan Rhodesia[53]

Rhodesia[53] Seychelles[54]

Seychelles[54] Shanghai Municipal Police[20]

Shanghai Municipal Police[20] Siam[20]

Siam[20] Sierra Leone[54][55]

Sierra Leone[54][55] Singapore: Retired

Singapore: Retired Switzerland

Switzerland Tunisia: Retired

Tunisia: Retired Tanzania[56]

Tanzania[56] Union of South Africa[57]

Union of South Africa[57] Zimbabwe[58]

Zimbabwe[58]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Dabbs, Will (January 17, 2022). "The webley revolver: Sidearm of an Empire". The Armory Life.

- ^ "Historic firearm of the month", July 1999, Cruffler.com. Retrieved on 2006-12-02

- ^ Ficken, Homer R. "Webley's 'The British Bull Dog' Revolver: Serial Numbering and Variations". Archived from the original on 2012-02-23. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

- ^ a b Kinard, Jeff (2004). Pistols: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-85109-470-7.

- ^ Ficken, Homer R. "Webley's 'The British Bull Dog' Revolver: Serial Numbering and Variations". Archived from the original on 2012-02-23. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

- ^ List of Changes in British War Material (hereafter referred to as "List of Changes"), H.M. Stationer's Office, periodical § 6075

- ^ Skennerton 1997, p. 6

- ^ Maze 2002, p. 44

- ^ a b Dowell 1987, p. 115

- ^ Dowell 1987, p. 114

- ^ Dowell 1987, p. 116

- ^ "Webley 1890" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-15. Retrieved 2011-08-19.

- ^ Utting, Nigel. "Magazine Loader for Rapidly Loading Revolvers: A historical review" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2011-08-19.

- ^ Dowell 1987, p. 178

- ^ Maze 2002, p. 49

- ^ a b Smith 1979, p. 11

- ^ Stamps & Skennerton 1993, p. 87

- ^ Stamps & Skennerton 1993, p. 117

- ^ Stamps & Skennerton 1993, p. 119

- ^ a b c d e Maze 2012, p. 57.

- ^ "Cartridge SA .380" Ball Revolver". Indian Ordnance Factories. Retrieved 2006-08-03.

- ^ "Revolver 32 (7.65 mm x 23)". Indian Ordnance Factories. Retrieved 2006-08-03.

- ^ List of Changes § 7816[full citation needed]

- ^ List of Changes § 9039

- ^ List of Changes § 9787

- ^ List of Changes § 16783

- ^ List of Changes § 17319

- ^ Skennerton 1997, p. 10

- ^ Stamps & Skennerton 1993, p. 9

- ^ Maze 2002, p. 103

- ^ § A6862, LoC

- ^ § B2289, LoC

- ^ § B6712, LoC

- ^ Stamps & Skennerton 1993, p. 12

- ^ Custer's last Gun Webley RIC revolver Guns and Ammo Magazine

- ^ Maze 2002, p. 30

- ^ Elman, Robert (1968). Fired In Anger. Doubleday. OCLC 436122.

- ^ Doerner, John A. "Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn". Martin Pate. Archived from the original on 2003-09-24. Retrieved 2006-08-03.

- ^ Gallear, Mark (2001). "Guns at the Little Bighorn". Custer Association of Great Britain. Archived from the original on 2006-09-08. Retrieved 2006-08-03.

- ^ Ficken, Homer R. "Webley's The British Bull Dog Revolver, Serial Numbering and Variations". Archived from the original on 2012-02-23. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- ^ Kekkonen, P.T. "British Bulldog revolver". Gunwriters. Retrieved 2006-08-03.

- ^ Dowell 1987, p. 128

- ^ Maze 2002, p. 78

- ^ a b Maze 2012, p. 59.

- ^ Weeks 1980, p. 658.

- ^ Hogg 1988, p. 766.

- ^ Bishop, Chris (1998). Guns in Combat. Chartwell Books. ISBN 0-7858-0844-2.

- ^ a b Maze 2012, pp. 63−70.

- ^ Maze 2012, p. 58.

- ^ Weeks 1980, p. 664.

- ^ "Weapons of the Police and Auxiliary Forces in Malaya".

- ^ Maung, Aung Myoe (2009). Building the Tatmadaw: Myanmar Armed Forces Since 1948. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-230-848-1.

- ^ Walther, P.P.K. Rhodesia's Hangover: An African Dilemma. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-4567-8485-0.

- ^ a b Hogg 1988, p. 772.

- ^ "World Infantry Weapons: Sierra Leone". 2013. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016.

- ^ "World Infantry Weapons: Tanzania". Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Maze 2012, pp. 58−59.

- ^ Hogg 1988, p. 775.

References

[edit]- Dowell, William Chipchase (1987). The Webley Story. Kirkland, WA: Commonwealth Heritage Foundation. ISBN 0-939683-04-0.

- H.M. Stationer's Office, List of Changes in British War Material, H.M.S.O, London, Periodical.

- Maze, Robert J. (2002). Howdah to High Power: A Century of Breechloading Service Pistols (1867–1967). Tucson, AZ: Excalibur. ISBN 1-880677-17-2.

- Skennerton, Ian D. (1997). .455 Pistol, Revolver No. 1 Mk VI. Small Arms Identification Series. Vol. 9. Gold Coast, QLD (Australia): Arms & Militaria Press. ISBN 0-949749-30-3.

- Smith, W.H.B. (1979). 1943 Basic Manual of Military Small Arms. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-1699-6.

- Stamps, Mark; Skennerton, Ian D. (1993). .380 Enfield Revolver No. 2. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-139-8.

- Wilson, Royce (March 2006). "A Tale of Two Collectables". Australian Shooter. ISSN 1442-7354.

- Henrotin, Gerard (2007). The Webley service revolvers. Belgium: H&L Publishing.

- Maze, Robert (2012). The Webley Service Revolver. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-84908-804-6. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

- Weeks, John, ed. (1980). Jane's infantry weapons, 1980-81. Jane's Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-531-03936-6.

- Hogg, Ian V., ed. (1988). Jane's Infantry Weapons, 1988-89. Jane's Information Group. ISBN 978-0-7106-0857-4.

External links

[edit]- The Weapons Collection: Pistols Revolver, REME Museum of Technology.

- Historical Overview of the Webley Mk 4 Revolver from American Rifleman

- (1947) E.B. 962 – Identification List for Pistol, Revolver, Webley, .38-inch, Mark 4[permanent dead link]

- Webley revolver Model VI internal mechanism (technical drawing)